Article

Using Legal Funding for Home Modifications After Catastrophic Injury

Call for free evaluation

Available 24/7

Table of Content

On This Page

- Making the house livable again, fast

- Home modifications aren’t “nice to have”

- Where advances can actually help

- How funders assess permanence and necessity

- Contractor invoices, bids, and the “show me the numbers” part

- Rural homes, long drives, and getting the right vendors

- When long-term disability becomes the backdrop

- Exploitation cases and modifications that protect safety

- Status concerns can shape housing choices

- So what actually helps an advance request land well?

More Articles

Categories

Making the house livable again, fast

Catastrophic injury does this brutal thing: it changes the definition of “home” overnight.

One day, your front steps are just… steps. The next, they’re a wall. A full-on barrier between you and your own couch, your own bed, your own bathroom. It’s wild how fast ordinary architecture turns into a problem you can’t ignore.

And people try to “make it work” for a while. They do the awkward carry. The risky hop. The sponge bath situation nobody wants to talk about. They sleep on the first floor because the stairs are a joke now. They tell themselves it’s temporary—until the weeks stack up and the body doesn’t bounce back the way everyone hoped.

That’s usually when the conversation shifts from medical bills to something more immediate and, honestly, more human: how do we make this space safe enough to live in?

Home modifications aren’t “nice to have”

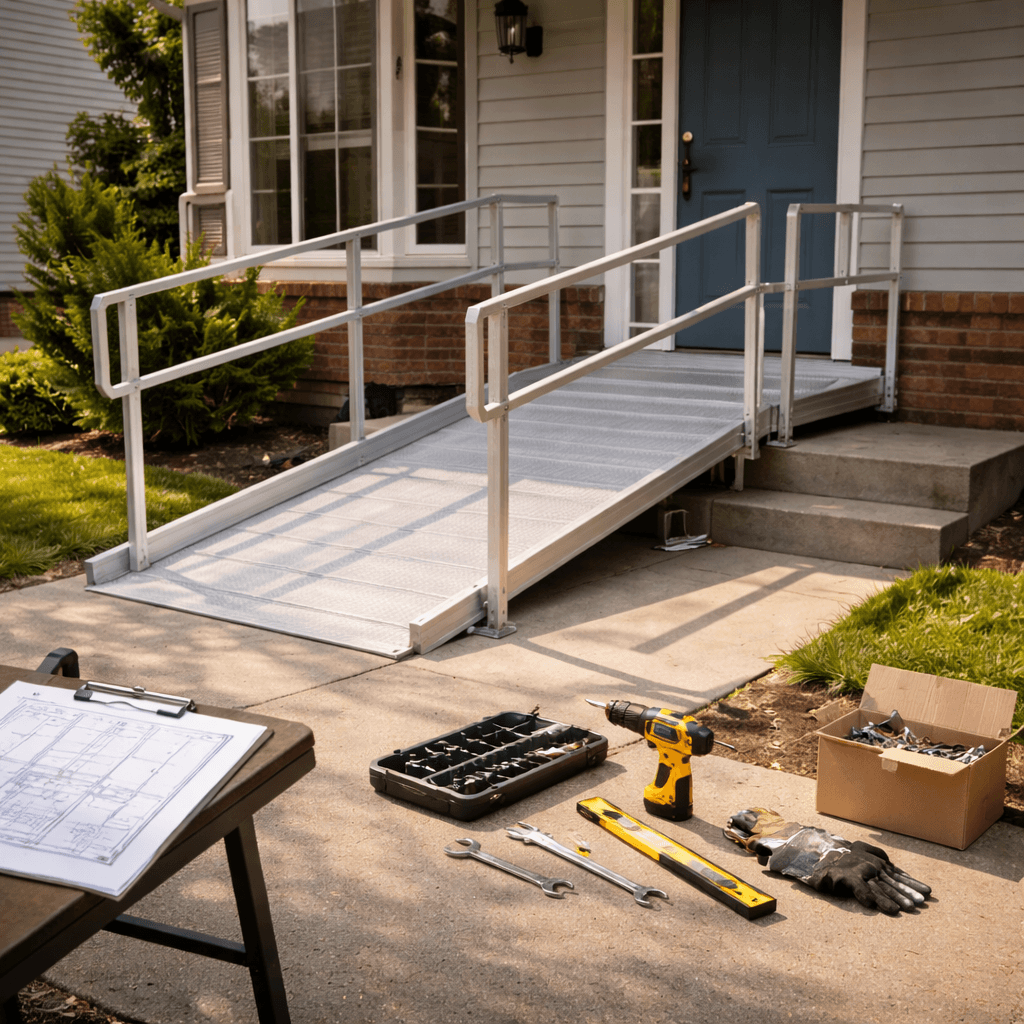

Ramps. Bathroom renovations. Doorway widening. Lift systems. Stair lifts. Roll-in showers. Grab bars placed where they actually help, not where some generic plan says they should go.

Adaptive equipment too—hospital beds, transfer boards, wheelchairs that fit the layout, pressure-relief mattresses, vehicle hand controls, that sort of thing. Some of it is straightforward. Some of it costs more than people expect, and that surprise hits hard when income has already taken a punch.

Is it commonly thought that “insurance will handle it”? Because that’s not always how it plays out. Coverage can be partial, delayed, denied, or wrapped in so much paperwork that you’d think the forms are the real product being sold.

Meanwhile, daily life is happening. The injured person needs access now. The caregiver needs a setup that doesn’t wreck their back in three months. The family needs fewer emergencies, fewer falls, fewer “we almost dropped you but didn’t” moments that haunt you at 2 a.m.

Where advances can actually help

When a case is pending and the timeline is long (and it almost always is), some plaintiffs look at an advance to cover modifications that can’t wait. The idea isn’t fancy. It’s practical: get the house functional so treatment and recovery can happen without the home itself being a hazard.

A ramp is the obvious one. But ramps are rarely just a plank and a prayer. They may require permits, railings, proper slope, landings, and weatherproofing. Same with bathrooms—once you start talking about a roll-in shower, you’re often talking plumbing, waterproofing, tile, drainage, maybe moving walls. Suddenly it’s a real project.

Lift systems can be even more complex. Ceiling track lifts. Vertical platform lifts. Stair lifts that fit the stairs you actually have, not the stairs someone imagines on a brochure. And if you’re renting? That adds another layer of negotiation and limitation. Home isn’t always “yours” in the simple sense.

That’s why funding decisions tend to hinge on something basic: is this modification medically tied to the injury, and is it a reasonable part of stabilizing the person’s day-to-day functioning?

How funders assess permanence and necessity

Funding review usually starts with the medical picture. Not just diagnosis, but permanence.

Temporary injuries can be serious, sure, but home modifications are often about long-term limitations: paralysis, amputations, traumatic brain injury with mobility and balance issues, severe spinal damage, complex regional pain syndrome that doesn’t let go, and so on. The more clearly the records show lasting impairment, the more a modification request makes sense as part of damages and future needs.

That’s where life-care plans come in. They’re not poetry. They’re not fun reading. But they can be incredibly persuasive because they translate injury into a structured forecast: what care is needed, what equipment is needed, what home setup is needed, and what it costs over time.

If a life-care planner says a roll-in shower and widened doorways are medically appropriate, that tends to carry weight—especially when paired with PT/OT notes explaining fall risk, transfer limitations, or caregiver requirements.

And yes, consistency matters. Treatment gaps can make any claim feel fuzzier, even if the gap happened for reasons that make total sense in real life. If someone paused therapy because transportation fell apart, or because the home setup made leaving the house miserable, the paper trail needs that context. Otherwise the silence gets filled in by assumptions. That’s the uncomfortable truth behind how breaks in care can affect decision-making: why interruptions tend to raise questions.

Contractor invoices, bids, and the “show me the numbers” part

Here’s what surprises people: underwriting isn’t allergic to home modification requests. But it is allergic to vague requests.

“We need a bathroom remodel” is a cloud. “We have two bids: $18,400 and $21,950 for a roll-in shower conversion, widened doorway to 36 inches, grab bars, non-slip flooring, and plumbing relocation” is a document.

Contractor bids, invoices, scope-of-work descriptions—these help set an anchor for the amount requested. Photos help too. Simple ones. Front steps, narrow hallway, existing bathroom layout. Nothing dramatic. Just clear.

And if you can tie the scope to medical recommendations, even better. Occupational therapy home assessments are gold here. Same with discharge instructions that specify mobility devices or home safety changes.

One detail people overlook: timelines. If a contractor says they can start next week and need a deposit, that’s part of the story. If the project will take six weeks and requires temporary relocation, that matters too. Not because anyone wants to fund chaos, but because catastrophic injury already comes with plenty of chaos… and planning reduces it.

Rural homes, long drives, and getting the right vendors

Home modification logistics get weirder in rural areas. Sometimes there’s one contractor within 40 miles who does accessible builds. Sometimes the nearest durable medical equipment provider is two counties over. Sometimes you’re paying extra just to get someone to come out and measure.

And then add the travel for medical care on top of it. If you’re already driving hours to specialists, the last thing you need is a house that makes transfers unsafe or showering impossible. Rural claimants often carry both burdens at once: distance to treatment and distance to the services that make home livable. That combination can shape damages and necessity in a way that’s hard to appreciate unless you’ve lived it: how travel realities can become part of the financial strain.

Also—keep those travel receipts. Gas, lodging, mileage logs. It’s all part of the injury’s footprint on your life.

When long-term disability becomes the backdrop

Catastrophic injuries often end up intersecting with disability, even if nobody wants that word in the room at first.

People hold onto work as long as they can. They reduce hours. They switch roles. They try again. Then the body makes the decision for them.

During that transition, home modifications can feel like both a necessity and a scary acknowledgment. Like, “If we install a lift, are we admitting this is forever?” That’s a heavy emotional layer to a practical project.

But financially, there can be a gap between “injury happened” and “benefits stabilize.” Claims take time. Disability determinations take time. Everyone seems to take time. So bridging that period matters, especially when the home needs immediate work to prevent falls and complications. That whole bridge-to-stability challenge shows up a lot when people are trying to cover life while long-term disability catches up: how some plaintiffs manage the in-between.

Exploitation cases and modifications that protect safety

There’s another scenario that doesn’t get discussed enough: catastrophic injury in the context of vulnerability—especially older plaintiffs.

If someone is dealing with elder abuse or financial exploitation, the home environment can be part of the harm, and modifications can be part of the safety plan. Better locks. Safer bathing. Reduced dependence on someone who can’t be trusted. Even moving to a different residence, which is its own cost spiral.

In those cases, the “home modification” conversation isn’t just about ramps. It’s about protection and autonomy. And the documentation often has to capture more than medical need—it has to capture risk. That overlap is common in the kind of cases where exploitation and injury collide: stabilizing situations when safety and finances are tangled.

Status concerns can shape housing choices

Sometimes families are navigating immigration worries in the background, and it affects everything—where they rent, who they’ll invite into the home, what paperwork they’re comfortable providing, even whether they’ll push for formal home assessments.

That doesn’t mean modifications aren’t needed. It means the process has to be handled carefully, with respect for privacy and real-world risk. People in that position often try to keep the case moving without adding exposure, while still getting the care and home setup that makes recovery possible: when injury recovery intersects with status anxiety.

It’s one of those things that sounds abstract until you’re living it, and then it’s not abstract at all.

So what actually helps an advance request land well?

Clarity beats intensity.

Provide medical support showing functional limitations and why the modification is needed. Add life-care plan excerpts if available. Include OT/PT notes referencing home safety or equipment needs. Then attach contractor bids, invoices, and scope-of-work documents that show real numbers, not guesses.

If the injury is permanent or likely permanent, make sure the records say so. If it’s still evolving, explain that too—because sometimes interim solutions (temporary ramps, rental equipment) are appropriate while the long-term plan takes shape.

And keep the story aligned: the home modification should match the injury limitations, and the costs should match the documented scope. Simple. Not always easy, but simple.

Some plaintiffs consider pre settlement funding specifically because modifications can’t be delayed without real risk—falls, infections, caregiver injuries, stalled recovery. The case will settle when it settles. The stairs don’t wait.

That’s the whole point, really. Making the environment match the new reality, so the person can focus on healing instead of surviving their own hallway.

Never settle for less. See how we can get you the funds you need today.

Call for free evaluation Available 24/7